- Joined

- Aug 29, 2021

- Messages

- 3,142

- Reaction score

- 26,506

- Awards

- 352

The Civil Conflict

The civil war in Guatemala is the result of critical limitations on democracy during three decades of military rule that began in 1954, when a democratic movement anticipated the development of revolutionary armed movements a decade later. Comprehensive Peace Accords signed in December 1996 ended the war and were the result of six years of United Nations-sponsored negotiations and an unprecedented openness by civil society.

The origins of the internal conflict - deep-rooted inequality, ethnic discrimination and the lack of political space for opposition - continued to fuel the conflict, so much so that war became the norm. Beginning in the 1960s, a new counterinsurgency policy in the form of state terror and scattered repression tried to quell opposition in any way. Cold War politics played a very critical role, as did the US government's use of Central America as a lever against the Soviet Union and as a means of implementing anti-communist policies through aid and proven covert operations. A United Nations-backed Commission for Historical Clarification (CEH) found that the military committed 93 percent of human rights violations during the war, including hundreds of massacres of civilians. As many as 200,000 people were killed or disappeared during the war.

The reasons for the war.

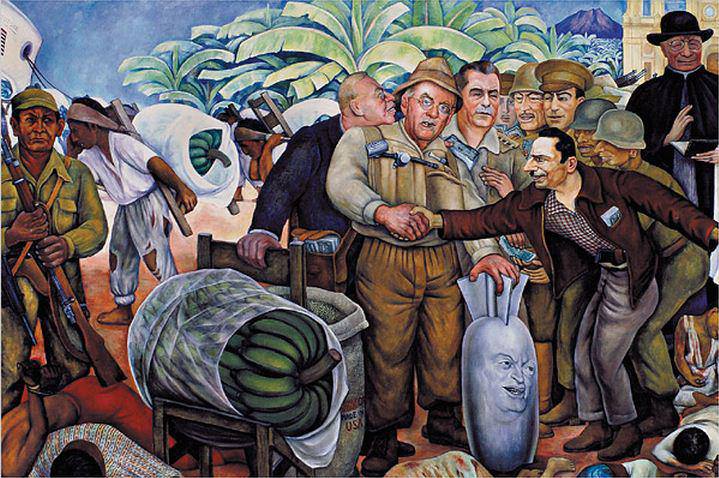

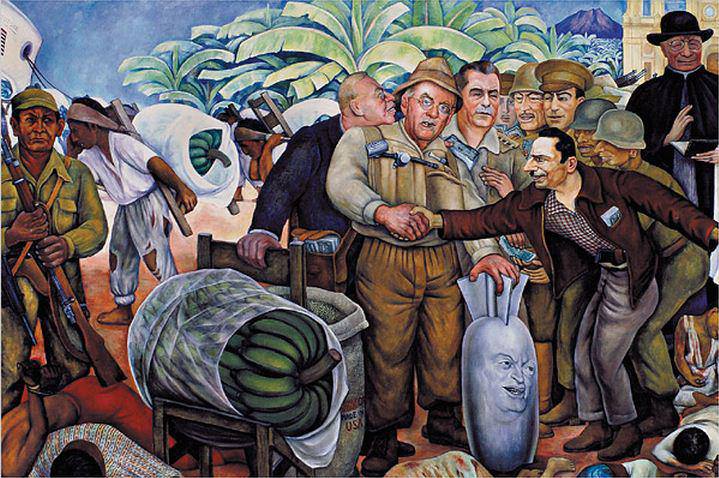

The directors of the United Fruit Company (UFCO) had worked intensively in the government circles of Harry S. Truman and General Dwight Eisenhower to make them believe that Colonel Árbenz was trying to align Guatemala with the Soviet Bloc. What happened was that the UFCO saw its economic interests threatened by Árbenz's agrarian reform, which took away significant amounts of idle land, and the new Guatemalan Labor Code, which no longer allowed it to use Guatemalan military forces to counter the demands of her workers. As Guatemalan's largest landowner and employer, Decree 900 resulted in the expropriation of 40% of her land. US government officials had little evidence of the growing communist threat in Guatemala , but he did have a strong relationship with the representatives of the UFCO: the US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles belonged to the law firm Sullivan and Cromwell (in English) which had already represented the interests of United Fruit and made negotiations with Guatemalan governments; his brother Allen Dulles was the director of the CIA and a member of the board of directors of the UFCO; the brother of the Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs John Moors Cabot had been president of the fruit company and Ed Whitman, who was United Fruit's chief lobbyist to the US government, was married to President Eisenhower's personal secretary, Ann C. Whitman.

For their part, the US government and the Guatemalan right-wing accused Árbenz of being a communist for having attacked the interests of US monopolies in Guatemala, because members of his private circle were leaders of the communist Guatemalan Labor Party (PGT).

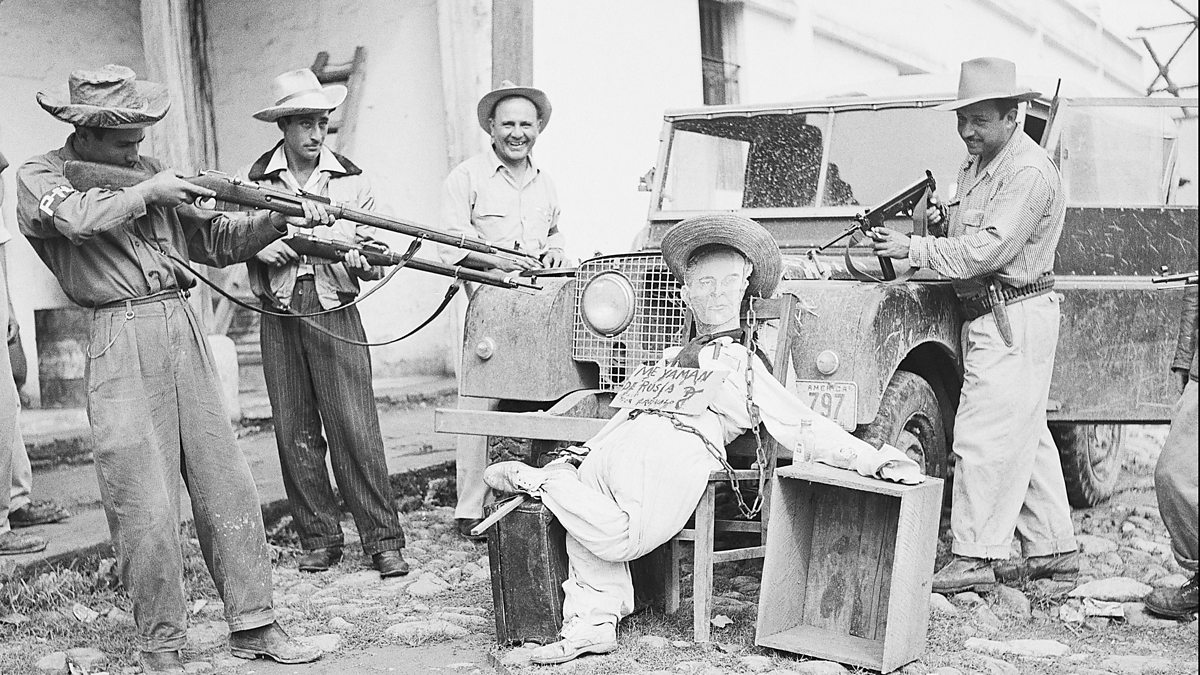

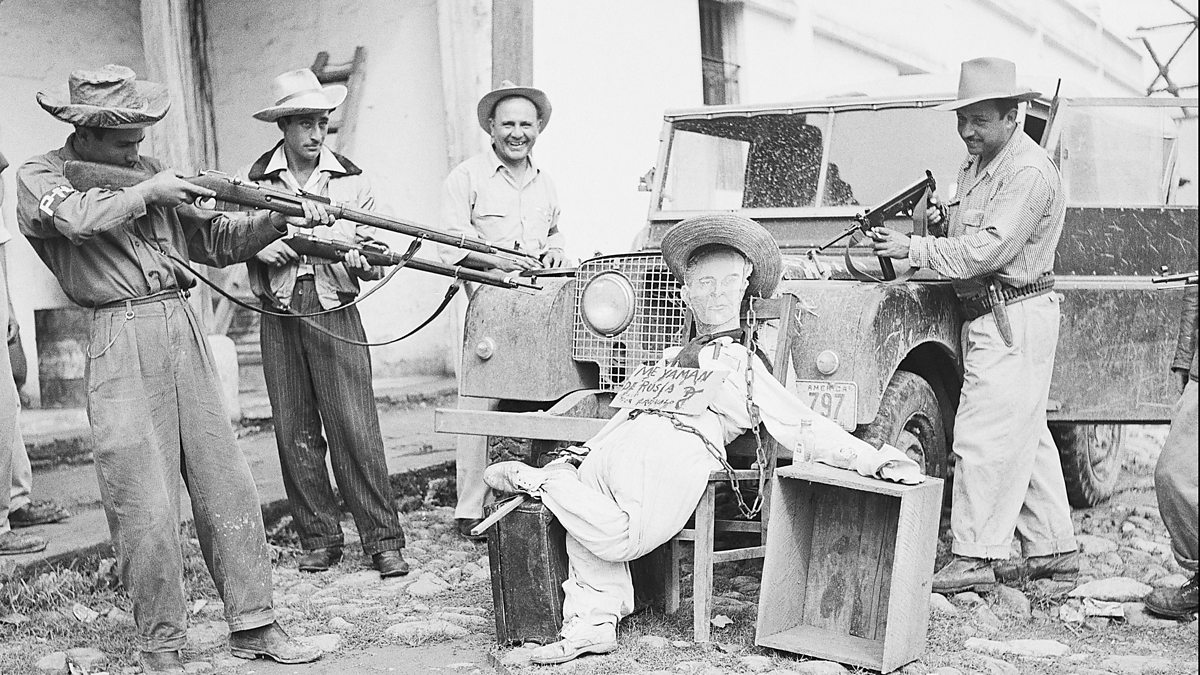

in the beginning of 1953, a plan prepared by American experts was launched to expel Árbenz from the Government, establishing the operational headquarters in Opa Locka, Florida. In August 1953, J.C. King, CIA chief for the Western Hemisphere, briefed the US president on the Operation PBSUCCESS plan (with an initial budget of $3 million), which consisted of deploying a huge anti-communist propaganda operation in the that an armed invasion of Guatemala would also take place. The project had the active support of the dictators of the Caribbean basin: Anastasio Somoza (Nicaragua), Marcos Pérez Jiménez (Venezuela) and Rafael Leónidas Trujillo (Dominican Republic). In this way, the CIA was the one that organized, financed and directed a covert operation in which flights of B-26s and P-47s from Nicaragua were even authorized.

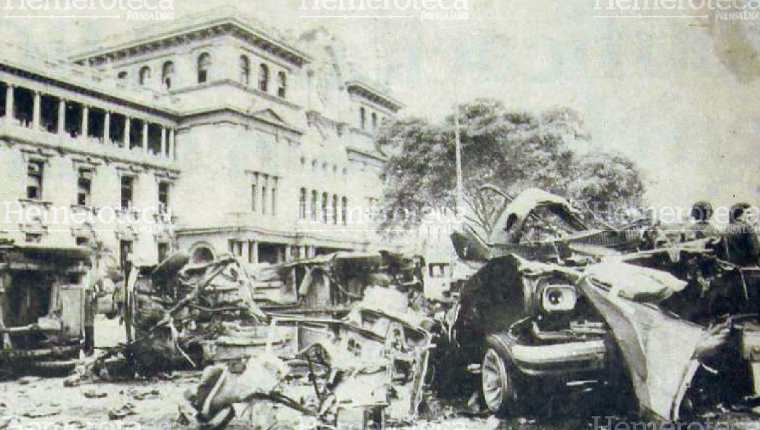

During the month of June 1954, Guatemala lived in a climate of irremediable confrontation. In the countryside, land invasions happened one after another, while rallies and demonstrations in support of the regime were fewer and fewer. The sermons and warnings of the Church intensified and a series of signs appeared in the main cities of eastern Guatemala, reading: "Liberation Day: those who support Castillo Armas will live, those who support Árbenz will die."The bombardment of the capital and other urban areas was initially resisted by the Army, but the effects of the attack blew its effectiveness among officials and politicians ―both civilian and military― and in different sectors of the Guatemalan population. Planes and radio propaganda spread discontent and, above all, softened the will of the Arbenz regime. Finally, seeing the passivity of the army in the face of the weak invasion, Árbenz resigned in July 1954.

After the 1954 counterrevolution, the Guatemalan government created the Economic Planning Council (CNPE) and began using free market strategies, advised by the World Bank and the United States government's International Cooperation Administration (ICA). The CNPE and the ICA created the General Directorate of Agrarian Affairs (DGAA) which was in charge of dismantling and annulling the effects of Decree 900 on Agrarian Reform of the government of Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán. In 1959, the decree law was approved, it created the National Company for the Promotion and Economic Development of Petén (FYDEP), a dependency of the Presidency of the Republic, and that would be in charge of the colonization process of the department of Petén; in practice, the FYDEP was directed by the military and was a dependency of the Ministry of Defense;in parallel, the DGAA was in charge of the geographical strip that adjoined the departmental limit of Petén and the borders of Belize, Honduras and Mexico, and that over time would be called Franja Transversal del Norte (FTN).

Civil War

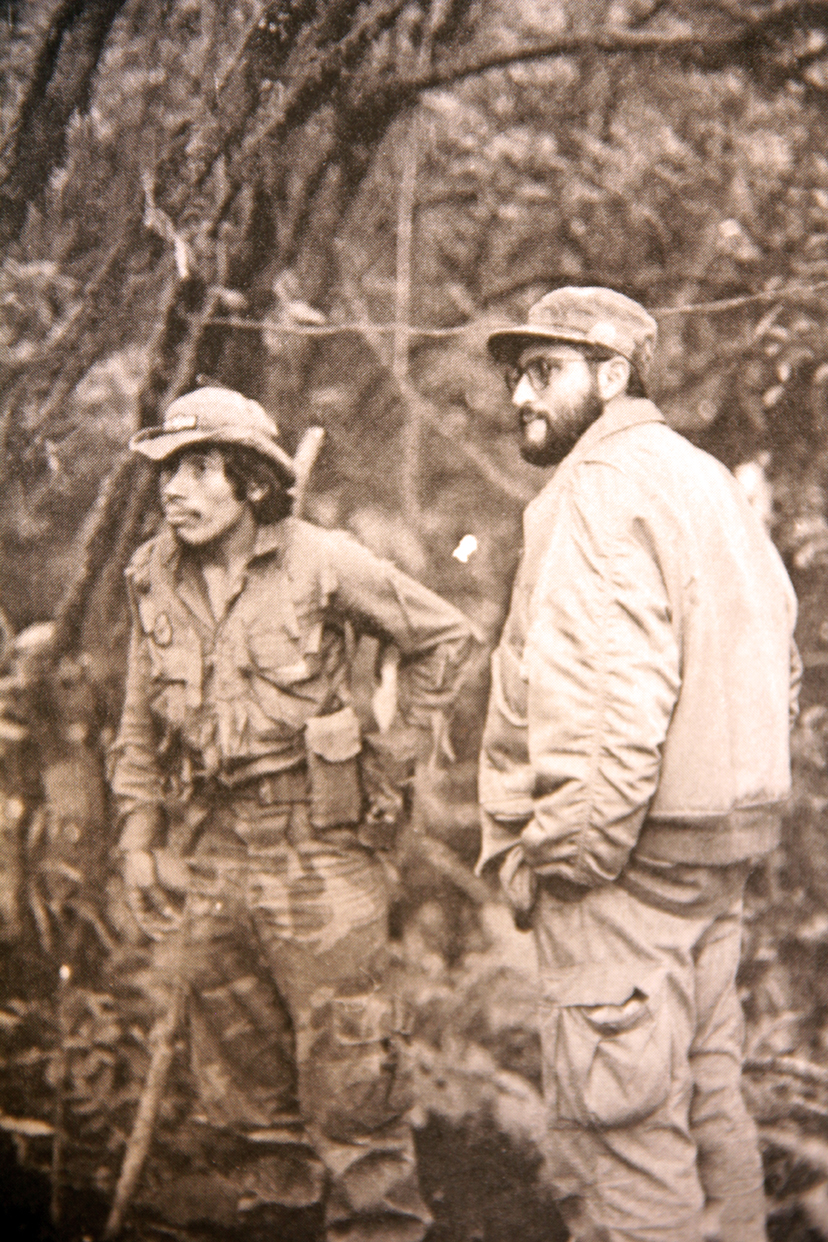

On February 7, 1962, a small group of young rebels led by Yon Sosa and Turcios Lima joined together with Julio César Macías, creating the November 13 Revolutionary Movement (MR-13); Among its members also appears Pablo Monsanto, who was also known by the nickname "Manzana" (apple). The group thus opened a new type of political struggle in the country by forming the November 13 Revolutionary Movement (MR-13) in order to overthrow the government through arms; For this they contacted the political groups, especially the PGT, to establish alliances. The political crisis continued and the government opened many flanks, thus beginning the guerrilla struggle in Guatemala.

After the founding of the MR-13 in February 1962, a year passes and the Rebel Armed Forces (FAR) are created in a small traditional Chinese restaurant in Guatemala City: on February 7, 1963, the year that began in chaos with protest movements and strikes by postal and health workers, gathered at the Fu Lu Sho restaurant on 6th. avenue and 12 street in zone 1, just six blocks from the National Palace, Yon Sosa, Turcios Lima, and civilians Bernardo Alvarado Monzón, Mario Silva Jonama, Joaquín Noval and Bernardo Lemus. They agreed to publicly publicize the creation of the FAR, integrating the representation of the November 13 Movement, the Guatemalan Labor Party and the April 12 Movement, naming Commander Yon Sosa as military chief of the organization.

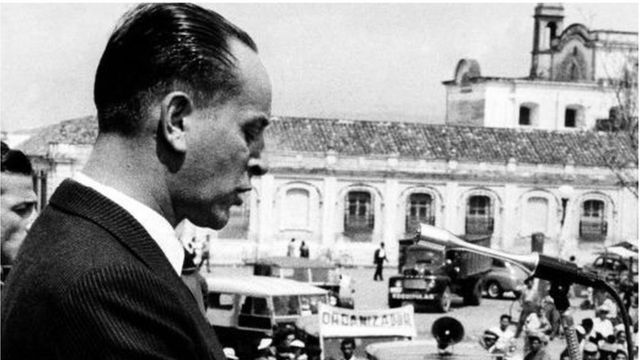

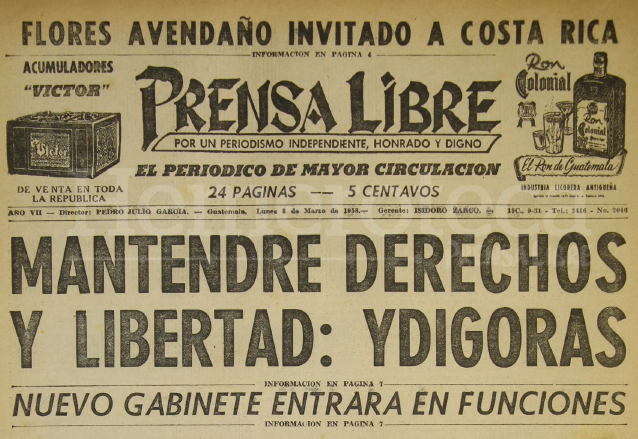

1963 Coup

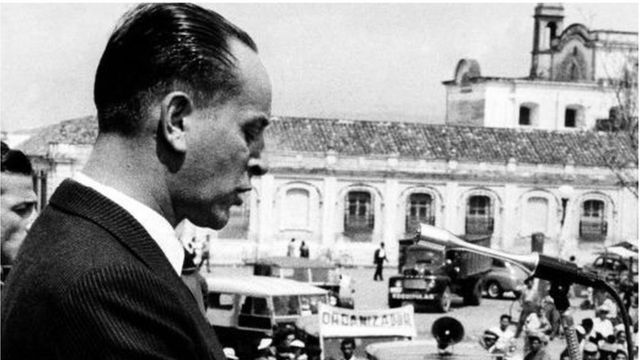

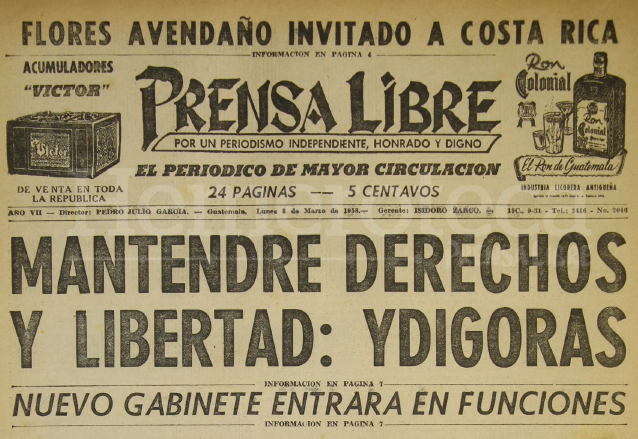

With the Ydígoras government on a tightrope, this one, to calm things down, authorized the former president, the socialist Juan José Arévalo, leader around whom the entire left was unified, to return to the country and be a candidate for the 1963 elections, and so he could be elected president for the period 1964-1970. The leadership of the Guatemalan Army and the most conservative upper classes of society strongly opposed it, fearing the possibility of repeating the experience of 1944-1954. At the end of March, the rumors that Arévalo would enter the country increased. On March 29, all the country's newspapers published the news on their front pages that Juan José Arévalo was in Guatemala. The next day, in the early morning of March 30, 1963, Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes was overthrown by his Minister of Defense, Colonel Enrique Peralta Azurdia, who immediately declared a state of siege and, thinking that the electoral victory of Juan José Arévalo was certain and Inevitably, he annulled the 1963 elections, accusing Ydigoras of being about to hand over power into the hands of the enemy. Ydígoras was expelled from the country to Panama.

With the 1963 coup d'état, the Guatemalan Army, as an institution, assumed absolute control of the State, thus establishing a military dictatorship, and promised to crush the insurgency once and for all, especially the guerrillas that were attacking in the east of the country. Enrique Peralta Azurdia repealed the Political Constitution of the Republic, dissolved Congress, prohibited political association and absolutely blocked the left from all political activity, increasing its persecution. He also continued to serve as Defense Minister.

During the government of Peralta Azurdia, a new paramilitary force of the Guatemalan Army was also created, called the "Escuadrones de la Muerte" (Death Squads), which would be in charge of kidnapping and assassinating opponents. It was from his government that a series of kidnappings began. , torture and selective murders ―mainly in the Capital―, against intellectuals, trade unionists, artists, writers, students, teachers and any other political opponents, as well as those who were collaborators or simply sympathizers with leftist groups; but the left did not sit idly by: on April 1, 1965, several people were injured and public and private buildings were damaged after several terrorist attacks by the Rebel Armed Forces while Peralta Azurdia presented to congress his report on the two years of his military government. The attacks were directed at military offices and the building of the Congress of the Republic, where at that time the Constituent Assembly was working, which was writing the new constitution; a bomb exploded three hundred meters from the presidential house, and another two were activated in residences of deputies in the south of Guatemala City.

The Church and Theology Liberation

Theology Liberation is a theological current that began together with the "Second Vatican Council" within the Catholic Church in Latin America and in some Protestant churches. The axis of liberation theology is the poor; The poor become the subject and the underlying theme of liberation theology not for political, social or economic reasons, but fundamentally for Biblical theological reasons. Consequently, the Church, if it is true Church, is a Church of the poor.

At the beginning of the 1970s, several parishes in the diocese of Escuintla, on the South Coast of Guatemala, began social pastoral work through the so-called Families of God, inspired by the pedagogy of Paulo Freire. This work addressed the study of the Bible from the perspective of the poor, oriented towards reflection on the role of Christians in building a more just society. One aspect of concern for the Catholic Church on the South Coast was the inhumane working conditions on the farms and the lack of organization for temporary workers and crews from the Altiplano.

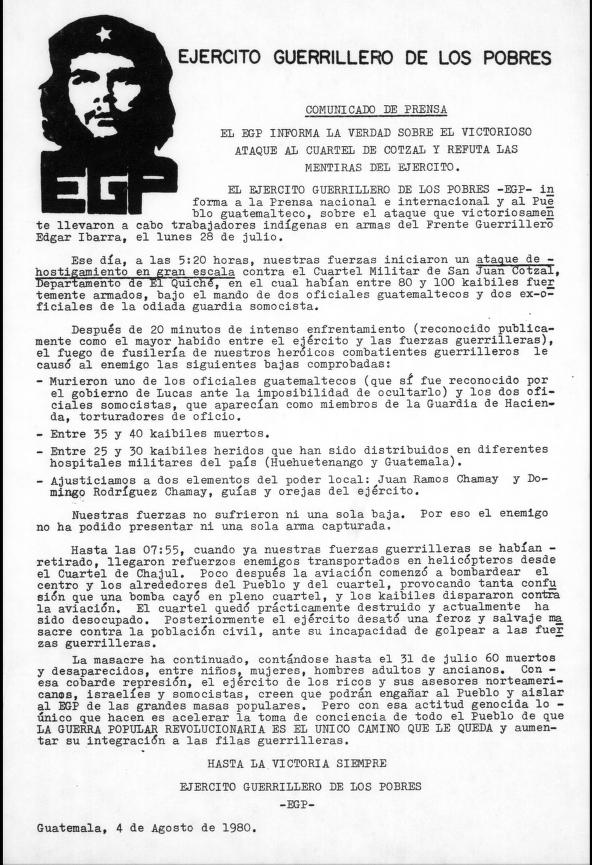

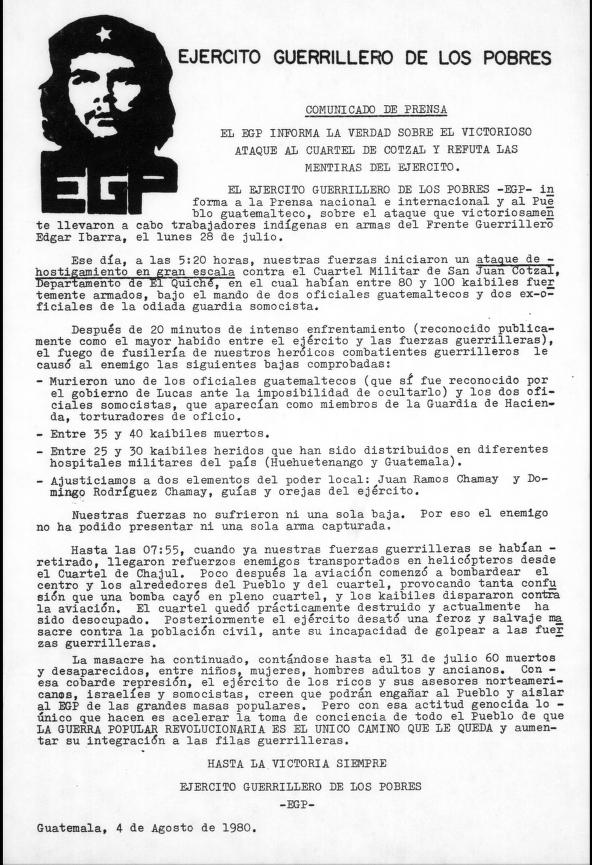

According to publications of the Army of Guatemala, by the year 1980 the EGP fronts had reached a very high level of organization, with the support and intervention of Jesuit priests, Maryknoll and Missionaries of the Sacred Heart; These foreign priests, mostly Spanish, through Catholic Action, would have put together a framework perfectly designed by liberation theologians ―Javier Gurriarán (parish priest of Santa María Nebaj); Marcelino García (parish priest of San Juan Cotzal); and Manuel Antonio González (parish priest of San Gaspar Chajul)― obtaining with his intervention and indoctrination, a broad domain over the communities of the Ixil Triangle.

All this effort of religious involvement was coordinated, from another guerrilla front, by Luis Gurriaránab and Ricardo Falla Sánchez, the religious were thus in charge of developing a recruitment strategy for the EGP. This strategy, based on the theory and praxis of the church of the poor, used among its procedures to increase its influence visits and constant indoctrination meetings. According to the army reports, these ideologues directed in this way the indoctrination through the theology of liberation, through more than one hundred priests and nuns of different religious orders, together with the EGP.

Guerilla Reformation.

After the crushing defeat guerillas suffered at the end of 1968, a change in mentality occurred on the part of the insurgency, which led it to abandon to a great extent the Castroist inspiration of the 1960s, to adopt an ideology much more nationalist and indigenous. This change caused a division within the Rebel Armed Forces that were in crisis, forming the Guerrilla Army of the Poor, which arises at the beginning of 1972 and had the peculiarity of having the support of Catholics committed to the poor related to the Theology of the Liberation.

With the secret support of the Mexican government, this group of dissidents moved to that country in order to clandestinely enter Guatemala from the Northwest and create a primary guerrilla focus from which to continue the armed struggle until the seizure of power. The area is chosen taking into account the little development of its infrastructures and therefore, the little military presence in addition to being a region of very poor peasant and indigenous implantation, which they considered as the main engine of the Revolution.

After a long time of preparation, the first guerrilla column to arrive from Mexico would enter Guatemala through the Ixcán jungle, north of the department of El Quiché near the La Candón river, to extend to the rest of El Quiché and Huehuetenango. From the beginning they were concerned about not being detected by the Army, while at the same time they undertook work to establish a base of support among the population, all with great precautions so that it did not happen to them like the guerrillas of the previous decade that were defeated.

Leftist groups had learned several lessons from the first failed attempts in the Guatemalan Oriente:

But despite the fact that the guerrillas were clear about all this, they failed in all aspects: they managed to involve the indigenous people and carried out a constant psychological campaign that had an effect originally, but when the years passed and no results were seen, the indigenous people were disappointed. of the guerrillas and began to see the Guatemalan army in better shape. On the other hand, the guerrillas never found the appropriate language or managed to fulfill the promises to improve the living conditions of the peasantry, causing greater disappointment among the indigenous population. Lastly, the guerrillas never had a large army, and their attacks on army commandos resulted in the army taking it out on civilian populations, for not being able to directly pursue the insurgents.

With the advent of the Guerrilla Army of the Poor, the town's civilian populations found themselves between two fires: the army repressed those it considered guerrilla collaborators, and vice versa. There were cases of massacres by guerrillas against civil patrolmen, with the excuse that the latter were traitors to their people; and there were also cases of abuse by patrolmen, who took advantage of their position to settle personal or ethnic issues with neighboring towns. As a result of the harassment to which they were subjected by both sides, many peasants took refuge in Mexico and did not return until 1993 (This happened to my dad, who managed to avoid the draft), during the government of engineer Jorge Serrano Elías.

Nicaraguan embassador got killed by the EGP

In October 1977, the Guerrilla Army of the Poor shot at the Nicaraguan ambassador in Guatemala, Edmundo Meneses, who died of his wounds after two weeks. The attack was due to the solidarity of the GAP (EGP) with the Sandinista guerrilla that at that time was fiercely fighting the Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle.

The civil war in Guatemala is the result of critical limitations on democracy during three decades of military rule that began in 1954, when a democratic movement anticipated the development of revolutionary armed movements a decade later. Comprehensive Peace Accords signed in December 1996 ended the war and were the result of six years of United Nations-sponsored negotiations and an unprecedented openness by civil society.

The origins of the internal conflict - deep-rooted inequality, ethnic discrimination and the lack of political space for opposition - continued to fuel the conflict, so much so that war became the norm. Beginning in the 1960s, a new counterinsurgency policy in the form of state terror and scattered repression tried to quell opposition in any way. Cold War politics played a very critical role, as did the US government's use of Central America as a lever against the Soviet Union and as a means of implementing anti-communist policies through aid and proven covert operations. A United Nations-backed Commission for Historical Clarification (CEH) found that the military committed 93 percent of human rights violations during the war, including hundreds of massacres of civilians. As many as 200,000 people were killed or disappeared during the war.

The reasons for the war.

The directors of the United Fruit Company (UFCO) had worked intensively in the government circles of Harry S. Truman and General Dwight Eisenhower to make them believe that Colonel Árbenz was trying to align Guatemala with the Soviet Bloc. What happened was that the UFCO saw its economic interests threatened by Árbenz's agrarian reform, which took away significant amounts of idle land, and the new Guatemalan Labor Code, which no longer allowed it to use Guatemalan military forces to counter the demands of her workers. As Guatemalan's largest landowner and employer, Decree 900 resulted in the expropriation of 40% of her land. US government officials had little evidence of the growing communist threat in Guatemala , but he did have a strong relationship with the representatives of the UFCO: the US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles belonged to the law firm Sullivan and Cromwell (in English) which had already represented the interests of United Fruit and made negotiations with Guatemalan governments; his brother Allen Dulles was the director of the CIA and a member of the board of directors of the UFCO; the brother of the Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs John Moors Cabot had been president of the fruit company and Ed Whitman, who was United Fruit's chief lobbyist to the US government, was married to President Eisenhower's personal secretary, Ann C. Whitman.

For their part, the US government and the Guatemalan right-wing accused Árbenz of being a communist for having attacked the interests of US monopolies in Guatemala, because members of his private circle were leaders of the communist Guatemalan Labor Party (PGT).

in the beginning of 1953, a plan prepared by American experts was launched to expel Árbenz from the Government, establishing the operational headquarters in Opa Locka, Florida. In August 1953, J.C. King, CIA chief for the Western Hemisphere, briefed the US president on the Operation PBSUCCESS plan (with an initial budget of $3 million), which consisted of deploying a huge anti-communist propaganda operation in the that an armed invasion of Guatemala would also take place. The project had the active support of the dictators of the Caribbean basin: Anastasio Somoza (Nicaragua), Marcos Pérez Jiménez (Venezuela) and Rafael Leónidas Trujillo (Dominican Republic). In this way, the CIA was the one that organized, financed and directed a covert operation in which flights of B-26s and P-47s from Nicaragua were even authorized.

During the month of June 1954, Guatemala lived in a climate of irremediable confrontation. In the countryside, land invasions happened one after another, while rallies and demonstrations in support of the regime were fewer and fewer. The sermons and warnings of the Church intensified and a series of signs appeared in the main cities of eastern Guatemala, reading: "Liberation Day: those who support Castillo Armas will live, those who support Árbenz will die."The bombardment of the capital and other urban areas was initially resisted by the Army, but the effects of the attack blew its effectiveness among officials and politicians ―both civilian and military― and in different sectors of the Guatemalan population. Planes and radio propaganda spread discontent and, above all, softened the will of the Arbenz regime. Finally, seeing the passivity of the army in the face of the weak invasion, Árbenz resigned in July 1954.

After the 1954 counterrevolution, the Guatemalan government created the Economic Planning Council (CNPE) and began using free market strategies, advised by the World Bank and the United States government's International Cooperation Administration (ICA). The CNPE and the ICA created the General Directorate of Agrarian Affairs (DGAA) which was in charge of dismantling and annulling the effects of Decree 900 on Agrarian Reform of the government of Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán. In 1959, the decree law was approved, it created the National Company for the Promotion and Economic Development of Petén (FYDEP), a dependency of the Presidency of the Republic, and that would be in charge of the colonization process of the department of Petén; in practice, the FYDEP was directed by the military and was a dependency of the Ministry of Defense;in parallel, the DGAA was in charge of the geographical strip that adjoined the departmental limit of Petén and the borders of Belize, Honduras and Mexico, and that over time would be called Franja Transversal del Norte (FTN).

Civil War

On February 7, 1962, a small group of young rebels led by Yon Sosa and Turcios Lima joined together with Julio César Macías, creating the November 13 Revolutionary Movement (MR-13); Among its members also appears Pablo Monsanto, who was also known by the nickname "Manzana" (apple). The group thus opened a new type of political struggle in the country by forming the November 13 Revolutionary Movement (MR-13) in order to overthrow the government through arms; For this they contacted the political groups, especially the PGT, to establish alliances. The political crisis continued and the government opened many flanks, thus beginning the guerrilla struggle in Guatemala.

After the founding of the MR-13 in February 1962, a year passes and the Rebel Armed Forces (FAR) are created in a small traditional Chinese restaurant in Guatemala City: on February 7, 1963, the year that began in chaos with protest movements and strikes by postal and health workers, gathered at the Fu Lu Sho restaurant on 6th. avenue and 12 street in zone 1, just six blocks from the National Palace, Yon Sosa, Turcios Lima, and civilians Bernardo Alvarado Monzón, Mario Silva Jonama, Joaquín Noval and Bernardo Lemus. They agreed to publicly publicize the creation of the FAR, integrating the representation of the November 13 Movement, the Guatemalan Labor Party and the April 12 Movement, naming Commander Yon Sosa as military chief of the organization.

1963 Coup

With the Ydígoras government on a tightrope, this one, to calm things down, authorized the former president, the socialist Juan José Arévalo, leader around whom the entire left was unified, to return to the country and be a candidate for the 1963 elections, and so he could be elected president for the period 1964-1970. The leadership of the Guatemalan Army and the most conservative upper classes of society strongly opposed it, fearing the possibility of repeating the experience of 1944-1954. At the end of March, the rumors that Arévalo would enter the country increased. On March 29, all the country's newspapers published the news on their front pages that Juan José Arévalo was in Guatemala. The next day, in the early morning of March 30, 1963, Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes was overthrown by his Minister of Defense, Colonel Enrique Peralta Azurdia, who immediately declared a state of siege and, thinking that the electoral victory of Juan José Arévalo was certain and Inevitably, he annulled the 1963 elections, accusing Ydigoras of being about to hand over power into the hands of the enemy. Ydígoras was expelled from the country to Panama.

With the 1963 coup d'état, the Guatemalan Army, as an institution, assumed absolute control of the State, thus establishing a military dictatorship, and promised to crush the insurgency once and for all, especially the guerrillas that were attacking in the east of the country. Enrique Peralta Azurdia repealed the Political Constitution of the Republic, dissolved Congress, prohibited political association and absolutely blocked the left from all political activity, increasing its persecution. He also continued to serve as Defense Minister.

During the government of Peralta Azurdia, a new paramilitary force of the Guatemalan Army was also created, called the "Escuadrones de la Muerte" (Death Squads), which would be in charge of kidnapping and assassinating opponents. It was from his government that a series of kidnappings began. , torture and selective murders ―mainly in the Capital―, against intellectuals, trade unionists, artists, writers, students, teachers and any other political opponents, as well as those who were collaborators or simply sympathizers with leftist groups; but the left did not sit idly by: on April 1, 1965, several people were injured and public and private buildings were damaged after several terrorist attacks by the Rebel Armed Forces while Peralta Azurdia presented to congress his report on the two years of his military government. The attacks were directed at military offices and the building of the Congress of the Republic, where at that time the Constituent Assembly was working, which was writing the new constitution; a bomb exploded three hundred meters from the presidential house, and another two were activated in residences of deputies in the south of Guatemala City.

The Church and Theology Liberation

Theology Liberation is a theological current that began together with the "Second Vatican Council" within the Catholic Church in Latin America and in some Protestant churches. The axis of liberation theology is the poor; The poor become the subject and the underlying theme of liberation theology not for political, social or economic reasons, but fundamentally for Biblical theological reasons. Consequently, the Church, if it is true Church, is a Church of the poor.

At the beginning of the 1970s, several parishes in the diocese of Escuintla, on the South Coast of Guatemala, began social pastoral work through the so-called Families of God, inspired by the pedagogy of Paulo Freire. This work addressed the study of the Bible from the perspective of the poor, oriented towards reflection on the role of Christians in building a more just society. One aspect of concern for the Catholic Church on the South Coast was the inhumane working conditions on the farms and the lack of organization for temporary workers and crews from the Altiplano.

According to publications of the Army of Guatemala, by the year 1980 the EGP fronts had reached a very high level of organization, with the support and intervention of Jesuit priests, Maryknoll and Missionaries of the Sacred Heart; These foreign priests, mostly Spanish, through Catholic Action, would have put together a framework perfectly designed by liberation theologians ―Javier Gurriarán (parish priest of Santa María Nebaj); Marcelino García (parish priest of San Juan Cotzal); and Manuel Antonio González (parish priest of San Gaspar Chajul)― obtaining with his intervention and indoctrination, a broad domain over the communities of the Ixil Triangle.

All this effort of religious involvement was coordinated, from another guerrilla front, by Luis Gurriaránab and Ricardo Falla Sánchez, the religious were thus in charge of developing a recruitment strategy for the EGP. This strategy, based on the theory and praxis of the church of the poor, used among its procedures to increase its influence visits and constant indoctrination meetings. According to the army reports, these ideologues directed in this way the indoctrination through the theology of liberation, through more than one hundred priests and nuns of different religious orders, together with the EGP.

Guerilla Reformation.

After the crushing defeat guerillas suffered at the end of 1968, a change in mentality occurred on the part of the insurgency, which led it to abandon to a great extent the Castroist inspiration of the 1960s, to adopt an ideology much more nationalist and indigenous. This change caused a division within the Rebel Armed Forces that were in crisis, forming the Guerrilla Army of the Poor, which arises at the beginning of 1972 and had the peculiarity of having the support of Catholics committed to the poor related to the Theology of the Liberation.

With the secret support of the Mexican government, this group of dissidents moved to that country in order to clandestinely enter Guatemala from the Northwest and create a primary guerrilla focus from which to continue the armed struggle until the seizure of power. The area is chosen taking into account the little development of its infrastructures and therefore, the little military presence in addition to being a region of very poor peasant and indigenous implantation, which they considered as the main engine of the Revolution.

After a long time of preparation, the first guerrilla column to arrive from Mexico would enter Guatemala through the Ixcán jungle, north of the department of El Quiché near the La Candón river, to extend to the rest of El Quiché and Huehuetenango. From the beginning they were concerned about not being detected by the Army, while at the same time they undertook work to establish a base of support among the population, all with great precautions so that it did not happen to them like the guerrillas of the previous decade that were defeated.

Leftist groups had learned several lessons from the first failed attempts in the Guatemalan Oriente:

- It was necessary to involve the indigenous and not the ladino.

- In order to succeed, a mass uprising was needed.

- A constant psychological campaign had to be carried out on the indigenous population.

- It had to be shown that the guerrillas were identified with the just causes of the vast majority.

But despite the fact that the guerrillas were clear about all this, they failed in all aspects: they managed to involve the indigenous people and carried out a constant psychological campaign that had an effect originally, but when the years passed and no results were seen, the indigenous people were disappointed. of the guerrillas and began to see the Guatemalan army in better shape. On the other hand, the guerrillas never found the appropriate language or managed to fulfill the promises to improve the living conditions of the peasantry, causing greater disappointment among the indigenous population. Lastly, the guerrillas never had a large army, and their attacks on army commandos resulted in the army taking it out on civilian populations, for not being able to directly pursue the insurgents.

With the advent of the Guerrilla Army of the Poor, the town's civilian populations found themselves between two fires: the army repressed those it considered guerrilla collaborators, and vice versa. There were cases of massacres by guerrillas against civil patrolmen, with the excuse that the latter were traitors to their people; and there were also cases of abuse by patrolmen, who took advantage of their position to settle personal or ethnic issues with neighboring towns. As a result of the harassment to which they were subjected by both sides, many peasants took refuge in Mexico and did not return until 1993 (This happened to my dad, who managed to avoid the draft), during the government of engineer Jorge Serrano Elías.

Nicaraguan embassador got killed by the EGP

In October 1977, the Guerrilla Army of the Poor shot at the Nicaraguan ambassador in Guatemala, Edmundo Meneses, who died of his wounds after two weeks. The attack was due to the solidarity of the GAP (EGP) with the Sandinista guerrilla that at that time was fiercely fighting the Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle.