- Joined

- Sep 15, 2021

- Messages

- 1,717

- Reaction score

- 5,892

- Awards

- 301

Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

Widely considered to be one of the greatest works of literature ever written, the story centers on an extramarital affair between Anna and dashing cavalry officer Count Alexei Kirillovich Vronsky that scandalizes the social circles of Saint Petersburg and forces the young lovers to flee to Italy in a search for happiness, but after they return to Russia, their lives further unravel.

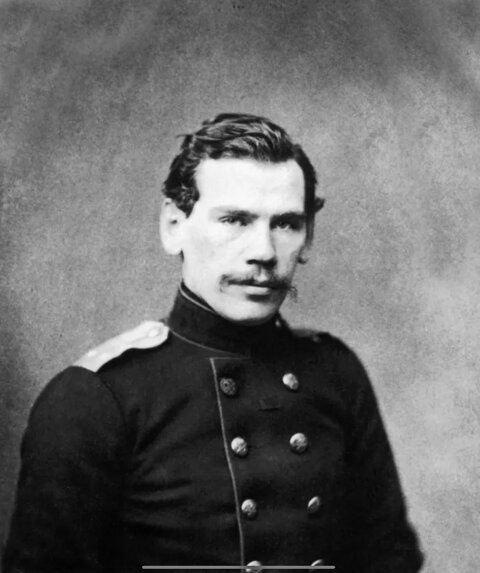

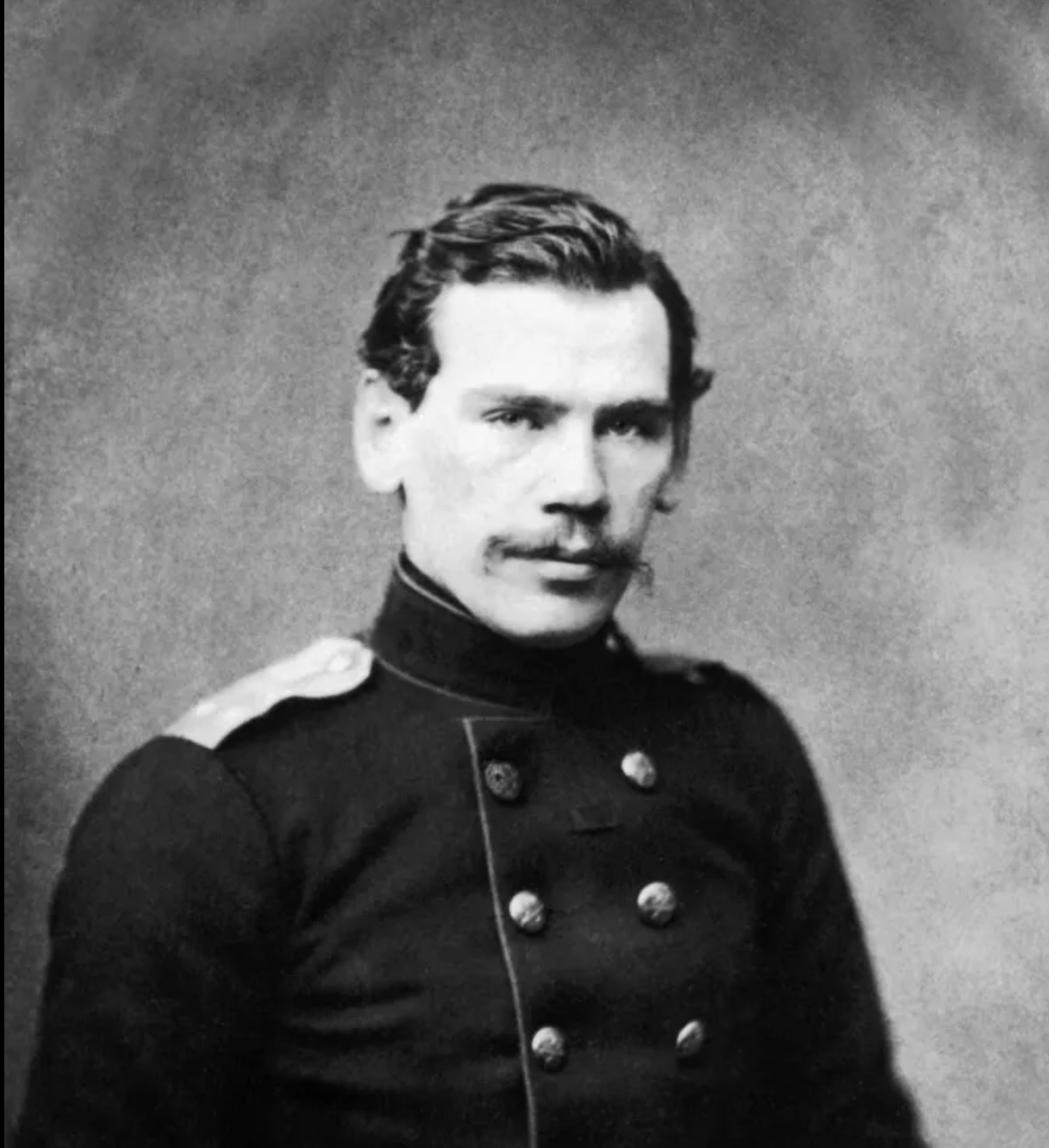

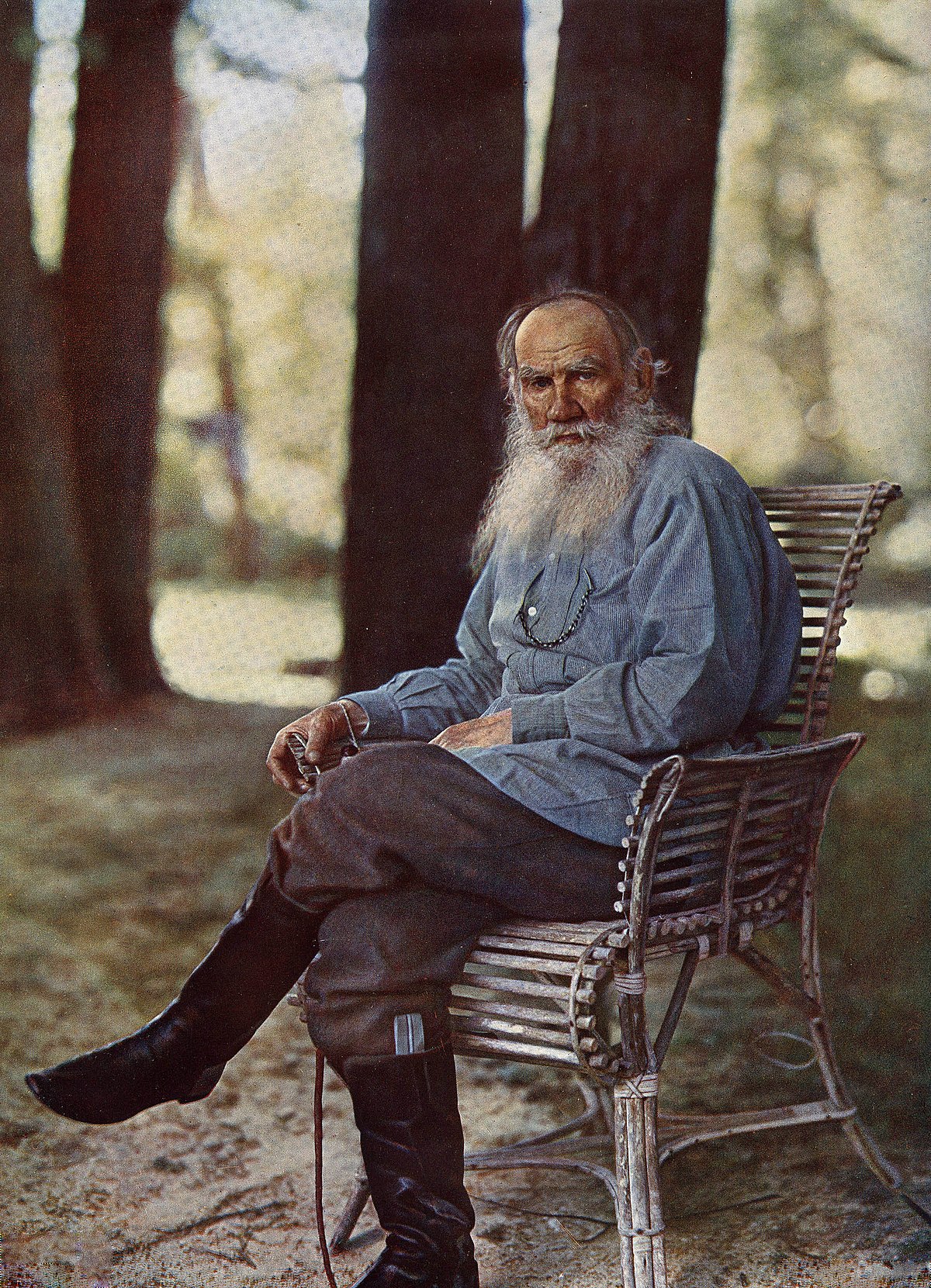

About Tolstoy (Taken from Encyclopedia Britannica)

Leo Tolstoy, Russian in full Lev Nikolayevich, Graf (count) Tolstoy, born August 28 , 1828, Yasnaya Polyana, Tula province, Russian Empire—died November 7 1910, Astapovo, Ryazan province.

The scion of prominent aristocrats, Tolstoy was born at the family estate, in August 28 1828, about 130 miles (210 kilometres) south of Moscow, where he was to live the better part of his life and write his most-important works. His mother, Mariya Nikolayevna, née Princess Volkonskaya, died before he was two years old, and his father Nikolay Ilich, Graf (count) Tolstoy, followed her in 1837. His grandmother died 11 months later, and then his next guardian, his aunt Aleksandra, in 1841. Tolstoy and his four siblings were then transferred to the care of another aunt in Kazan, in western Russia. Tolstoy remembered a cousin who lived at Yasnaya Polyana, Tatyana Aleksandrovna Yergolskaya ("Aunt Toinette," as he called her), as the greatest influence on his childhood, and later, as a young man. Despite the constant presence of death, Tolstoy remembered his childhood in idyllic terms. His first published work, Detstvo (1852; Childhood), was a fictionalized and nostalgic account of his early years.

Educated at home by tutors, Tolstoy enrolled in the University of Kazan in 1844 as a student of Oriental languages. His poor record soon forced him to transfer to the less-demanding law faculty. Interested in literature and ethics, he was drawn to the works of the English novelists Laurence Sterne and Charles Dickens and, especially, to the writings of the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau; in place of a cross, he wore a medallion with a portrait of Rousseau. But he spent most of his time trying to be comme il faut (socially correct), drinking, gambling, and engaging in debauchery. After leaving the university in 1847 without a degree, Tolstoy returned to Yasnaya Polyana, where he planned to educate himself, to manage his estate, and to improve the lot of his serfs. Despite frequent resolutions to change his ways, he continued his loose life during stays in Tula, Moscow, and St. Petersburg. In 1851 he joined his older brother Nikolay, an army officer, in the Caucasus and then entered the army himself. He took part in campaigns against the native peoples and, soon after, in the Crimean War (1853–56).

In 1847 Tolstoy began keeping a diary, which became his laboratory for experiments in self-analysis and, later, for his fiction. With some interruptions, Tolstoy kept his diaries throughout his life, and he is therefore one of the most copiously documented writers who ever lived. The early diaries record a fascination with rule-making, as Tolstoy composed rules for diverse aspects of social and moral behaviour. They also record the writer's repeated failure to honour these rules, his attempts to formulate new ones designed to ensure obedience to old ones, and his frequent acts of self-castigation.

After the Crimean War Tolstoy resigned from the army and was at first hailed by the literary world of St. Petersburg. But his prickly vanity, his refusal to join any intellectual camp, and his insistence on his complete independence soon earned him the dislike of the radical intelligentsia. He was to remain throughout his life an "archaist," opposed to prevailing intellectual trends. In 1857 Tolstoy traveled to Paris and returned after having gambled away his money.

After his return to Russia, he decided that his real vocation was pedagogy, and so he organized a school for peasant children on his estate. Tolstoy married Sofya Andreyevna Bers, the daughter of a prominent Moscow physician, in 1862 and soon transferred all his energies to his marriage and the composition of War and Peace. Tolstoy and his wife had 13 children, of whom 10 survived infancy.

Happily married and ensconced with his wife and family at Yasnaya Polyana, Tolstoy reached the height of his creative powers. He devoted the remaining years of the 1860s to writing War and Peace. Then, after an interlude during which he considered writing a novel about Peter the Great and briefly returned to pedagogy (bringing out reading primers that were widely used), Tolstoy wrote his other great novel, Anna Karenina. These two works share a vision of human experience rooted in an appreciation of everyday life and prosaic virtues.

Upon completing Anna Karenina, Tolstoy fell into a profound state of existential despair, which he describes in his Ispoved (1884; My Confession). All activity seemed utterly pointless in the face of death, and Tolstoy, impressed by the faith of the common people, turned to religion. Drawn at first to the Russian Orthodox church into which he had been born, he rapidly decided that it, and all other Christian churches, were corrupt institutions that had thoroughly falsified true Christianity. Having discovered what he believed to be Christ's message and having overcome his paralyzing fear of death, Tolstoy devoted the rest of his life to developing and propagating his new faith.

In the early 1880s, he wrote various essays on religion. In brief, Tolstoy rejected all the sacraments, all miracles, the Holy Trinity, the immortality of the soul, and many other tenets of traditional religion, all of which he regarded as obfuscations of the true Christian message contained, especially, in the Sermon on the Mount. He rejected the Old Testament and much of the New, which is why, having studied Greek, he composed his own "corrected" version of the Gospels. For Tolstoy, "the man Jesus," as he called him, was not the son of God but only a wise man who had arrived at a true account of life. He was excommunicated from the Russian Orthodox church in 1901.

Stated positively, the Christianity of Tolstoy's last decades stressed five tenets: be not angry, do not lust, do not take oaths, do not resist evil, and love your enemies. Nonresistance to evil, the doctrine that inspired Gandhi, meant not that evil must be accepted but only that it cannot be fought with evil means, especially violence. Thus, Tolstoy became a pacifist. Because governments rely on the threat of violence to enforce their laws, Tolstoy also became a kind of anarchist.

In defending his most-extreme ideas, Tolstoy compared Christianity to a lamp that is not stationary but is carried along by human beings; it lights up ever new moral realms and reveals ever higher ideals as mankind progresses spiritually.

In 1899 Tolstoy published his third long novel, Voskreseniye (Resurrection); he used the royalties to pay for the transportation of a persecuted religious sect, the Dukhobors, to Canada. The novel's most-celebrated sections satirize the church and the justice system, but the work is generally regarded as markedly inferior to War and Peace and Anna Karenina.

With the notable exception of his daughter Aleksandra, whom he made his heir, Tolstoy's family remained aloof from or hostile to his teachings. His wife especially resented the constant presence of disciples, led by the dogmatic V.G. Chertkov, at Yasnaya Polyana (Tolstoy's state). Their once happy life had turned into one of the most famous bad marriages in literary history.

Tormented by his domestic situation and by the contradiction between his life and his principles, in 1910 Tolstoy at last escaped incognito from Yasnaya Polyana, accompanied by Aleksandra and his doctor. In spite of his stealth and desire for privacy, the international press was soon able to report on his movements. Within a few days, he contracted pneumonia and died of heart failure on November 7th at the railroad station of Astapovo.

Some historical context: (Redacted from Wikipedia and Shmoop)

The events in the novel take place against the backdrop of rapid transformations as a result of the liberal reforms initiated by Emperor Alexander II of Russia, principal among these the Emancipation reform of 1861, followed by judicial reform, including a jury system; military reforms, the introduction of elected local governments (Zemstvo), the fast development of railroads, banks, industry, telegraph, the rise of new business elites and the decline of the old landed aristocracy, a freer press, the awakening of public opinion, the Pan-Slavism movement.

This was a time of insane amounts of intellectual fervor and debate about what direction Russia should take in becoming a modern nation. By the late 19th century, Russia was preoccupied in proving that it could be as advanced as the rest of Europe. This sparked a huge debate over how much Russia should try to Europeanize itself and how much it needed to hang onto its own traditional values.

At the same time, Russia was also dealing with huge economic and political issues. While Western countries were beginning to democratize, Russia was still an empire run by an all-powerful Czar. Russia's wealth was concentrated in the hands of a few wealthy nobles, but the vast majority of Russians were peasants who had been using the same farming techniques for hundreds of years. There were plenty of people who thought this situation was bad news, but there were lots of conflicting opinions on what should be done.

Some radicals suggested a violent overthrow of the tsar and the nobles. Other reformers wanted to try to solve the problem by making Russia more productive agriculturally. Some intellectuals looked to Western democracies to provide examples for Russia's future; they argued that education and modernization were essential.

Others dreamed of embracing a new social life based on ancient (and perhaps fictitious) Russian communal villages. Add to the mix traditional Orthodox Christianity and new stirrings of atheism, and you have a time period that would prove to be literally explosive.

A note on Russian names.

It was a pain to read through War and Peace for the first time because of how Russian names work. I thought like for 70% of the novel that there were way more characters than they actually were because of russian naming conventions, it made me be confused all the time.

Russians use patronymics in their personal names. A patronym is a composition based on your personal name and your father's name.

From wikipedia:

In Russian the endings -ovich, -evich and -ich are used to form patronymics for men. For women, the ending is -yevna, -ovna or -ichna. For example, in Russian, a man named Ivan with a father named Nikolay would be known as Ivan Nikolayevich or "Ivan, son of Nikolay" (Nikolayevich being a patronymic). Likewise, a woman named Lyudmila with a father named Nikolay would be known as Lyudmila Nikolayevna or "Lyudmila, daughter of Nikolay" (Nikolayevna being a patronymic).

So, an example from the novel. Anna's middle name is "Arkadyevna." meaning "daughter of Arkady." Her brother's middle name is "Arkadyevitch," meaning "son of Arkady."

From this we can deduce their father's name was "Arkady"

According to one >reddit user I found: Russians call each other by the Christian name and patronym, rarely by surname.

user I found: Russians call each other by the Christian name and patronym, rarely by surname.

Another important thing. Russian women usually take the surname of their husband when they marry. So Karenina comes from her husband's surname Karenin, plus the sufix 'na' because she's a woman.

Besides all of this, Russian has a bunch of naming conventions. Now i'll be honest, I couldn't gather how the grammar for these is supposed to work, and apparently there are no set rules for how to construct russian nicknames, since it varies a lot from name to name. But take into account that my source for this is a random quora user, so take that with a grain of salt. Anyways, idk how they work but you should know they exist. Here are some examples for the name Maria:

Maria: Full form of name, official, professional relationships, unfamiliar people.

Masha: Short form, neutral and used in casual relationships.

Mashenka: Form of affection.

Mashunechka, Mashunya and Marusya: Intimate, tender forms.

Mashka: Vulgar, impolite unless used inside the family, between children, or friends.

And a lit example, in Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoyevsky, the protagonist Raskolnikov's first name, Rodion, appears in the following forms: Rodya, Rodenka, and Rodka. His sister, Avdotya, is frequently referred to as Dunya and Dunechka.

In Brother's Karamazov Dimitri is often called Dima. Thankfully I wasn't as stupid and it took me only like 200 pages to figure out Dima and Dimitri were the same characters. But lmao I was for a while like, Ok. So. There are 5 brothers?

On translations (From Tolstoy Therapy)

For a Tolstoy-approved Anna Karenina, choose the Maude translation.

For a bestselling translation in American English, choose Pevear and Volokhonsky.

For an updated Anna Karenina that reads smoothly in British English, choose the Bartlett translation.

For an accurate and literal Anna Karenina that embraces Tolstoy's clunkiness, choose Schwartz's new translation.

Or you can be like me and pick it based on the bookcover.

Vote for your favorite book cover! (You can choose up to 3)

Old English edition

Leatherbound classics edition

Woodsworth Classics Edition:

Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition

Margelos World Republic of Letters Edition

1978 Penguin Edition

Alma Clasica (Spanish) Edition

Japanese Edition

Russian Edition

Russian Edition 2#

Happy Reading!

Widely considered to be one of the greatest works of literature ever written, the story centers on an extramarital affair between Anna and dashing cavalry officer Count Alexei Kirillovich Vronsky that scandalizes the social circles of Saint Petersburg and forces the young lovers to flee to Italy in a search for happiness, but after they return to Russia, their lives further unravel.

About Tolstoy (Taken from Encyclopedia Britannica)

Leo Tolstoy, Russian in full Lev Nikolayevich, Graf (count) Tolstoy, born August 28 , 1828, Yasnaya Polyana, Tula province, Russian Empire—died November 7 1910, Astapovo, Ryazan province.

The scion of prominent aristocrats, Tolstoy was born at the family estate, in August 28 1828, about 130 miles (210 kilometres) south of Moscow, where he was to live the better part of his life and write his most-important works. His mother, Mariya Nikolayevna, née Princess Volkonskaya, died before he was two years old, and his father Nikolay Ilich, Graf (count) Tolstoy, followed her in 1837. His grandmother died 11 months later, and then his next guardian, his aunt Aleksandra, in 1841. Tolstoy and his four siblings were then transferred to the care of another aunt in Kazan, in western Russia. Tolstoy remembered a cousin who lived at Yasnaya Polyana, Tatyana Aleksandrovna Yergolskaya ("Aunt Toinette," as he called her), as the greatest influence on his childhood, and later, as a young man. Despite the constant presence of death, Tolstoy remembered his childhood in idyllic terms. His first published work, Detstvo (1852; Childhood), was a fictionalized and nostalgic account of his early years.

Educated at home by tutors, Tolstoy enrolled in the University of Kazan in 1844 as a student of Oriental languages. His poor record soon forced him to transfer to the less-demanding law faculty. Interested in literature and ethics, he was drawn to the works of the English novelists Laurence Sterne and Charles Dickens and, especially, to the writings of the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau; in place of a cross, he wore a medallion with a portrait of Rousseau. But he spent most of his time trying to be comme il faut (socially correct), drinking, gambling, and engaging in debauchery. After leaving the university in 1847 without a degree, Tolstoy returned to Yasnaya Polyana, where he planned to educate himself, to manage his estate, and to improve the lot of his serfs. Despite frequent resolutions to change his ways, he continued his loose life during stays in Tula, Moscow, and St. Petersburg. In 1851 he joined his older brother Nikolay, an army officer, in the Caucasus and then entered the army himself. He took part in campaigns against the native peoples and, soon after, in the Crimean War (1853–56).

In 1847 Tolstoy began keeping a diary, which became his laboratory for experiments in self-analysis and, later, for his fiction. With some interruptions, Tolstoy kept his diaries throughout his life, and he is therefore one of the most copiously documented writers who ever lived. The early diaries record a fascination with rule-making, as Tolstoy composed rules for diverse aspects of social and moral behaviour. They also record the writer's repeated failure to honour these rules, his attempts to formulate new ones designed to ensure obedience to old ones, and his frequent acts of self-castigation.

After the Crimean War Tolstoy resigned from the army and was at first hailed by the literary world of St. Petersburg. But his prickly vanity, his refusal to join any intellectual camp, and his insistence on his complete independence soon earned him the dislike of the radical intelligentsia. He was to remain throughout his life an "archaist," opposed to prevailing intellectual trends. In 1857 Tolstoy traveled to Paris and returned after having gambled away his money.

After his return to Russia, he decided that his real vocation was pedagogy, and so he organized a school for peasant children on his estate. Tolstoy married Sofya Andreyevna Bers, the daughter of a prominent Moscow physician, in 1862 and soon transferred all his energies to his marriage and the composition of War and Peace. Tolstoy and his wife had 13 children, of whom 10 survived infancy.

Happily married and ensconced with his wife and family at Yasnaya Polyana, Tolstoy reached the height of his creative powers. He devoted the remaining years of the 1860s to writing War and Peace. Then, after an interlude during which he considered writing a novel about Peter the Great and briefly returned to pedagogy (bringing out reading primers that were widely used), Tolstoy wrote his other great novel, Anna Karenina. These two works share a vision of human experience rooted in an appreciation of everyday life and prosaic virtues.

Upon completing Anna Karenina, Tolstoy fell into a profound state of existential despair, which he describes in his Ispoved (1884; My Confession). All activity seemed utterly pointless in the face of death, and Tolstoy, impressed by the faith of the common people, turned to religion. Drawn at first to the Russian Orthodox church into which he had been born, he rapidly decided that it, and all other Christian churches, were corrupt institutions that had thoroughly falsified true Christianity. Having discovered what he believed to be Christ's message and having overcome his paralyzing fear of death, Tolstoy devoted the rest of his life to developing and propagating his new faith.

In the early 1880s, he wrote various essays on religion. In brief, Tolstoy rejected all the sacraments, all miracles, the Holy Trinity, the immortality of the soul, and many other tenets of traditional religion, all of which he regarded as obfuscations of the true Christian message contained, especially, in the Sermon on the Mount. He rejected the Old Testament and much of the New, which is why, having studied Greek, he composed his own "corrected" version of the Gospels. For Tolstoy, "the man Jesus," as he called him, was not the son of God but only a wise man who had arrived at a true account of life. He was excommunicated from the Russian Orthodox church in 1901.

Stated positively, the Christianity of Tolstoy's last decades stressed five tenets: be not angry, do not lust, do not take oaths, do not resist evil, and love your enemies. Nonresistance to evil, the doctrine that inspired Gandhi, meant not that evil must be accepted but only that it cannot be fought with evil means, especially violence. Thus, Tolstoy became a pacifist. Because governments rely on the threat of violence to enforce their laws, Tolstoy also became a kind of anarchist.

In defending his most-extreme ideas, Tolstoy compared Christianity to a lamp that is not stationary but is carried along by human beings; it lights up ever new moral realms and reveals ever higher ideals as mankind progresses spiritually.

In 1899 Tolstoy published his third long novel, Voskreseniye (Resurrection); he used the royalties to pay for the transportation of a persecuted religious sect, the Dukhobors, to Canada. The novel's most-celebrated sections satirize the church and the justice system, but the work is generally regarded as markedly inferior to War and Peace and Anna Karenina.

With the notable exception of his daughter Aleksandra, whom he made his heir, Tolstoy's family remained aloof from or hostile to his teachings. His wife especially resented the constant presence of disciples, led by the dogmatic V.G. Chertkov, at Yasnaya Polyana (Tolstoy's state). Their once happy life had turned into one of the most famous bad marriages in literary history.

Tormented by his domestic situation and by the contradiction between his life and his principles, in 1910 Tolstoy at last escaped incognito from Yasnaya Polyana, accompanied by Aleksandra and his doctor. In spite of his stealth and desire for privacy, the international press was soon able to report on his movements. Within a few days, he contracted pneumonia and died of heart failure on November 7th at the railroad station of Astapovo.

Some historical context: (Redacted from Wikipedia and Shmoop)

The events in the novel take place against the backdrop of rapid transformations as a result of the liberal reforms initiated by Emperor Alexander II of Russia, principal among these the Emancipation reform of 1861, followed by judicial reform, including a jury system; military reforms, the introduction of elected local governments (Zemstvo), the fast development of railroads, banks, industry, telegraph, the rise of new business elites and the decline of the old landed aristocracy, a freer press, the awakening of public opinion, the Pan-Slavism movement.

This was a time of insane amounts of intellectual fervor and debate about what direction Russia should take in becoming a modern nation. By the late 19th century, Russia was preoccupied in proving that it could be as advanced as the rest of Europe. This sparked a huge debate over how much Russia should try to Europeanize itself and how much it needed to hang onto its own traditional values.

At the same time, Russia was also dealing with huge economic and political issues. While Western countries were beginning to democratize, Russia was still an empire run by an all-powerful Czar. Russia's wealth was concentrated in the hands of a few wealthy nobles, but the vast majority of Russians were peasants who had been using the same farming techniques for hundreds of years. There were plenty of people who thought this situation was bad news, but there were lots of conflicting opinions on what should be done.

Some radicals suggested a violent overthrow of the tsar and the nobles. Other reformers wanted to try to solve the problem by making Russia more productive agriculturally. Some intellectuals looked to Western democracies to provide examples for Russia's future; they argued that education and modernization were essential.

Others dreamed of embracing a new social life based on ancient (and perhaps fictitious) Russian communal villages. Add to the mix traditional Orthodox Christianity and new stirrings of atheism, and you have a time period that would prove to be literally explosive.

A note on Russian names.

It was a pain to read through War and Peace for the first time because of how Russian names work. I thought like for 70% of the novel that there were way more characters than they actually were because of russian naming conventions, it made me be confused all the time.

Russians use patronymics in their personal names. A patronym is a composition based on your personal name and your father's name.

From wikipedia:

In Russian the endings -ovich, -evich and -ich are used to form patronymics for men. For women, the ending is -yevna, -ovna or -ichna. For example, in Russian, a man named Ivan with a father named Nikolay would be known as Ivan Nikolayevich or "Ivan, son of Nikolay" (Nikolayevich being a patronymic). Likewise, a woman named Lyudmila with a father named Nikolay would be known as Lyudmila Nikolayevna or "Lyudmila, daughter of Nikolay" (Nikolayevna being a patronymic).

So, an example from the novel. Anna's middle name is "Arkadyevna." meaning "daughter of Arkady." Her brother's middle name is "Arkadyevitch," meaning "son of Arkady."

From this we can deduce their father's name was "Arkady"

According to one >reddit

user I found: Russians call each other by the Christian name and patronym, rarely by surname.

user I found: Russians call each other by the Christian name and patronym, rarely by surname.Another important thing. Russian women usually take the surname of their husband when they marry. So Karenina comes from her husband's surname Karenin, plus the sufix 'na' because she's a woman.

Besides all of this, Russian has a bunch of naming conventions. Now i'll be honest, I couldn't gather how the grammar for these is supposed to work, and apparently there are no set rules for how to construct russian nicknames, since it varies a lot from name to name. But take into account that my source for this is a random quora user, so take that with a grain of salt. Anyways, idk how they work but you should know they exist. Here are some examples for the name Maria:

Maria: Full form of name, official, professional relationships, unfamiliar people.

Masha: Short form, neutral and used in casual relationships.

Mashenka: Form of affection.

Mashunechka, Mashunya and Marusya: Intimate, tender forms.

Mashka: Vulgar, impolite unless used inside the family, between children, or friends.

And a lit example, in Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoyevsky, the protagonist Raskolnikov's first name, Rodion, appears in the following forms: Rodya, Rodenka, and Rodka. His sister, Avdotya, is frequently referred to as Dunya and Dunechka.

In Brother's Karamazov Dimitri is often called Dima. Thankfully I wasn't as stupid and it took me only like 200 pages to figure out Dima and Dimitri were the same characters. But lmao I was for a while like, Ok. So. There are 5 brothers?

On translations (From Tolstoy Therapy)

For a Tolstoy-approved Anna Karenina, choose the Maude translation.

For a bestselling translation in American English, choose Pevear and Volokhonsky.

For an updated Anna Karenina that reads smoothly in British English, choose the Bartlett translation.

For an accurate and literal Anna Karenina that embraces Tolstoy's clunkiness, choose Schwartz's new translation.

Or you can be like me and pick it based on the bookcover.

Vote for your favorite book cover! (You can choose up to 3)

Old English edition

Leatherbound classics edition

Woodsworth Classics Edition:

Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition

Margelos World Republic of Letters Edition

1978 Penguin Edition

Alma Clasica (Spanish) Edition

Japanese Edition

Russian Edition

Russian Edition 2#

Happy Reading!